Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Hooray!

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

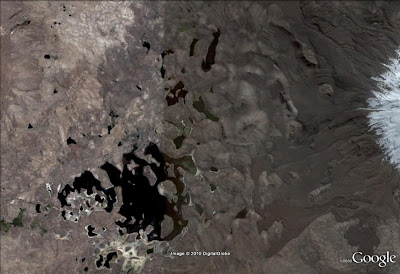

Where On (Google) Earth #181

Looks like I get to host the next episode of Where On Google Earth! Wo(G)E #180 over at Clastic Detritus turned out to be a tricky rotated image of the Farasan Banks, a huge coral reef complex off the coasts of Saudi Arabia and Yemen in the Red Sea. I don't know much about them beyond what I could dig up from a Jacques Cousteau quote:

"The wildest of all the reef complexes in the Red Sea … 350 miles long and thirty miles wide …. This demented masterpiece of outcrops, shoals, foaming reefs, and other lurking ship-breakers was created by societies of minute animals that have changed the aspect of our planet far more than man has yet been able to do."Anyone out there a coral reef expert? At any rate, I'm sure you're all waiting for the next challenge. Here it is:

Click to zoom. No altitude or direction on this one, but hopefully there are enough clues for you to track it down. To win the round, you need to post the correct latitude and longitude in the comments below, along with a little commentary about what geological feature you're looking at. The winner gets to host the next round, or choose the location and ask someone else to host it if they're not a blogger.

To give any newcomers a head start on this one, I'll invoke the Schott Rule- you have to wait one hour after the post time to answer for each WoGE round you've one in the past. Good luck!

PS - If you want to see where Wo(G)E has gone in the past (and who's won it), take a look at Ron Schott's compilation in KMZ format!

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Richter or not?

Most of you have probably heard about the earthquake that occurred in Haiti on Tuesday. It's shaping up to be a huge disaster, especially since it occurred in an area that hasn't seen a major earthquake for centuries; when natural disasters haven't occurred within living memory, people become unprepared to deal with them. The poverty of most of the millions of Haitians who were affected has only made it worse, and it's going to be a difficult recovery for them. I encourage everyone to find a charity that will be providing aid (the Red Cross, UNICEF, Doctors Without Borders, and Direct Relief International are just a few) or donate blood through the Red Cross. Even a few dollars or a little bit of blood will help.

It's only natural that a lot of news agencies will report natural disasters, and especially large earthquakes. But over and over again, I hear even the best reports making the same mistake: using the phrase "the earthquake was an X on the Richter scale." A Google News search for "Haiti earthquake Richter" brings up more than 500 references to news articles that use that phrase. It might seem nitpicky, but it always annoys me when the media can't be bothered to use the correct phrasing to describe earthquakes - it's a small misuse of scientific terminology, but if you take a closer look at it, it's a significant one.

The Richter magnitude scale was developed in 1935 by Charles F. Richter of the California Institute of Technology based on measurements made of shallow earthquakes in California. Technically, the way it was developed means that it's the most accurate in California, and when using a specific type of seismograph; it's also not terribly accurate for very large earthquakes or distant ones. Scientists have since expanded on the methods Richter used, which now incorporate even more data that can be recorded about an earthquake. The USGS website about "Earthquake Magnitude Policy" says it this way:

As far as the USGS is concerned - and they're usually the ones reporting earthquake magnitudes to the media - the preferred method of referring to magnitudes is with moment magnitude. Again, the USGS says it pretty succinctly:

Moment magnitude is measured on a logarithmic scale - each step up is many times more powerful than the last. This means that the 7.0 earthquake that happened in Haiti is much more powerful than, say, the ~M 5 earthquake that I felt in Guatemala earlier this year. When talking about earthquakes, official reports nowadays (like the USGS press releases) say the earthquake had a "magnitude of X". This is not to be confused with earthquake intensity, which measures the strength of shaking at any particular location, and is determined mainly by the earthquake's effects on people and structures. (An earthquake rating a I on the Mercalli Intensity Scale would be so small that almost no one would feel it, while the Haiti earthquake would be a VIII or higher, with significant or total destruction and visible effects during the shaking.)

So the takeaway message is to be careful how you talk about earthquake magnitude. If the information is coming from the USGS, it's referring to moment magnitude, and not the Richter scale. Hopefully some of the media will eventually pick up on this, for accuracy's sake if nothing else.

The Richter magnitude scale was developed in 1935 by Charles F. Richter of the California Institute of Technology based on measurements made of shallow earthquakes in California. Technically, the way it was developed means that it's the most accurate in California, and when using a specific type of seismograph; it's also not terribly accurate for very large earthquakes or distant ones. Scientists have since expanded on the methods Richter used, which now incorporate even more data that can be recorded about an earthquake. The USGS website about "Earthquake Magnitude Policy" says it this way:

"There is some confusion, however, about earthquake magnitude, primarily in the media, because seismologists often no longer follow Richter's original methodology. Richter's original methodology is no longer used because it does not give reliable results when applied to M> 7 earthquakes and it was not designed to use data from earthquakes recorded at epicentral distances greater than about 600 km. It is, therefore, useful to separate the method and the scale in releasing estimates of magnitude to the public."

"Moment is a physical quantity proportional to the slip on the fault times the area of the fault surface that slips; it is related to the total energy released in the EQ. The moment can be estimated from seismograms (and also from geodetic measurements). The moment is then converted into a number similar to other earthquake magnitudes by a standard formula. The result is called the moment magnitude. The moment magnitude provides an estimate of earthquake size that is valid over the complete range of magnitudes, a characteristic that was lacking in other magnitude scales."

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

The biggest bang for your buck

- Volume of material erupted (also called ejecta or tephra)

- Height of the eruptive column

- Qualitative descriptions (i.e., "effusive", "explosive", "paroxysmal")

- Classification (Hawaiian, Strombolian, Vulcanian, Plinian, Ultraplinian)

- Duration in hours

- The most explosive type of activity observed

- Tropospheric (up to ~10 km) and stratospheric (~10-50 km) injection of material (i.e., did the eruption column reach these atmospheric levels?

Ready, Steady, Blow! Volcano Betting Erupts! (Paddy Power website)

Newhall, C. and Self, S., 1982, The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI): An Estimate of Explosive Magnitude for Historical Volcanism. Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 87, no. C2, p. 1231-1238.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)